Why I Became an Atheist 04 – Bad reasons for belief (Part I)

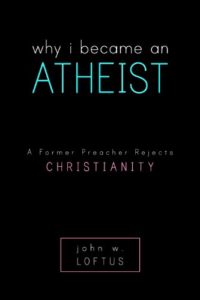

NOTE: This post is part of a series in which I am blogging my way through John Loftus’ book Why I Became an Atheist: A Former Preacher Rejects Christianity.

Last time, we examined John Loftus’ list of bad reasons to disbelieve, as well as his one GOOD reason – that of having adequate reasons to doubt.

Last time, we examined John Loftus’ list of bad reasons to disbelieve, as well as his one GOOD reason – that of having adequate reasons to doubt.

John also provides his own list of bad reasons for BELIEF (p. 36) – believing…

- from the need to be grateful to someone

- from the need for a God

- from weak intellectual foundations

- from the need to be committed

- in hopes of personal growth

- because of unruly emotions

- because of the fear of doubting

- believing from not being inquisitive enough

- believing from giving up too soon

Not surprisingly, John leaves off the same POSITIVE reason that Os Guinness left off of the list of bad reasons to doubt – that of having good REASONS.

I want to often repeat that there are good, rational reasons for both belief and unbelief, and even many atheists, such as Graham Oppy, admit such. The days of accusing our ideological adversaries of either mental or moral deficiency should be over.

But John’s list is worth discussing.

1. The need to be grateful to someone

On the surface, this seems like a trivial matter, and has taken the form of a joke that comes around every Thanksgiving:

At Thanksgiving, whom does an atheist thank?

But there is a deeper set of philosophic questions and assumptions beneath this innocuous motivation of needing to give thanks.

Question: are we self made, or do we acknowledge some greater dependence? And if so, upon whom? In his well-recieved book Living Without God: New Directions for Atheists, Agnostics, Secularists, and the Undecided, atheist Ronald Aronson addresses this ‘problem’:

Question: are we self made, or do we acknowledge some greater dependence? And if so, upon whom? In his well-recieved book Living Without God: New Directions for Atheists, Agnostics, Secularists, and the Undecided, atheist Ronald Aronson addresses this ‘problem’:

Hiking through a nearby woods on a late summer day recently, I followed the turning path and suddenly saw a pristine lake, then walked down a hill to its edge as birds chirped and darted about, stopping at a clearing to register the warmth of the sun against my face. Feelings welled up: physical pleasure, delight in the sounds and sights, gladness to be out here on this day. But something else as well, curious and less distinct, a vague feeling more like gratitude than anything else but not towards any being or person I could recognize. Only half-formed, this feeling didn’t fit into any easily discernable category, evading my usual lenses and language of perception.

Unfortunately, when trying to explain the feeling of gratitude when viewing the cosmos (the ‘creation’!), he has to sort of backpedal to explain that we should be thankful to the natural sources we are dependent upon – our culture, our family, perhaps even ‘nature,’ which is a non-personal, non-supernatural source for our dependence. The awe and transcendence we experience in such situations is warranted, but not attributable to any intelligence or personal, powerful God.

Feelings of dependence and of belonging are appropriate attitudes of response by the secular person…So are feelings of reverence and awe. None of these need be vague or fuzzy – if their worldly sources are not ignored and they are not projected beyond our universe, they become specific modes of living and experiencing our actual situation.

He admits this is ‘approrpiate’ for a secularist, but I’m not sure he addresses HOW. He also admits that this experience is awkward and hard to explain – and so, perhaps this ‘reason for believing’ is not as bad as John Loftus indicates. I can’t find Aronson’s published essay on this entitled “Thank you very much,” but here’s a review of it and his book by theologian Albert Mohler – Gratitude Without God.

Interestingly, the Apostle Paul wrote about this experience in Romans 1, explaining that this sense of awe is a primary evidence of God’s existence, enough that God is justified in condemning those who reject it as worthy evidence:

For since the creation of the world His invisible attributes are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even His eternal power and Godhead, so that they are without excuse, because, although they knew God, they did not glorify Him as God, nor were thankful, but became futile in their thoughts, and their foolish hearts were darkened. (Romans 1:20-21, NKJV)

But perhaps as a primary reason for believing, this evidence may be insufficient, I’ll grant John that. But as a primary evidence towards theism, I’m not sure this is such a bad reason to believe, or at least be open to belief.

2. The need for a God

Interestingly, this is one of the three major factors that caused me to return to faith after leaving it for many years.

I explored Buddhism, including a wonderful and difficult 10 day silent Vipassana retreat, where we did 11 hours of sitting meditation per day without any communications. And of course, you practice as if there is no God, just yourself and the universe.

But I had the strangest feeling near the end of that 10 days (which came at the end of many years of moving in that direction), and that was the whole ritual of practicing quietness without a God to talk to felt very unnatural – like I was ignoring the elephant in the room (you can read an entire essay on my Vipassana experience at Reflections on my 10 Day Silent Vipassana Retreat)

So, was my need for God just a psychological need, or did it reflect not only a genetic predisposition to commune with God, but the existence of something real that I was ignoring? There is just no way to tell for sure.

But that experience reminds me of another profound experience I had while walking on the beach many years ago, meditating on the following Bible passage:

Psalm 19:1-4 (NLT)

The heavens proclaim the glory of God.

The skies display his craftsmanship.Day after day they continue to speak;

night after night they make him known.They speak without a sound or word;

their voice is never heard.Yet their message has gone throughout the earth,

and their words to all the world.

As I was walking silently for a period of time, suddenly I had a shift of perception, where I felt like the whole creation was saying “God IS!, GOD IS!” Was this just auto-suggestion? Quite possibly, but it was profound. It was like suddenly hearing all of the noises of the forest after a time of stillness – after the business of life and one’s own thoughts settle in the quiet.

Even more, as a biochemistry and genetics major in undergrad, I came to be awed not only at the macro universe, but the micro one – the complexity is literally awe inspiring, and this awe seems to grow rather than diminish as we find out more about the micro world and its complexity.

But I don’t want to get into a teliological argument for the existence of God or the Intelligent Design debate – I just want to say that a felt ‘need for God’ may be just that, but it may also be a intuitional response to the reality of the divine, not just a mistake of the pscyche.

So again, I’d agree with John that this is not a logical reason, but neither is it exclusively a bad reason to *consider* the reality of the divine.

3. Weak intellectual foundations

I think John is right, but again, this is a double edged sword – while people may believe or disbelieve based on faulty data or logic, it can go either way. I think it is good to be able to found our beliefs on good thinking, and skepticism, logic, and empiricism will help.

But as Graham Oppy notes (I need to get a copy of this book instead of relying on the interviews I’ve heard with him), if reason and science could have definitively answered the question of God, there wouldn’t be large numbers of smart people still arguing from both sides – you’d have a few stragglers on one side or the other.

4. The need to be committed

I’m not exactly sure what John means by this, but if people are devoted to God in order to be devoted to something meaningful and larger than themselves, I must agree with him. There are plenty of organizations that do good in this world that have no religious foundations.

The Secondary Benefits of Religion

This last point, however, brings out an interesting distinction – many people ‘believe’ (or at least join churches) for the secondary benefits – community, friendship, commitment to social good. All of these are great benefits, but they have little to do with WHY we believe – but as Kenneth Daniels notes in Why I Believed: Reflections of a Former Missionary, these secondary benefits, or the fear of losing them, can certainly keep people from being skeptical about faith.

In my case the potential costs for leaving my faith served as a powerful disincentive to examining my beliefs clearly….The point I am making is that, all else being equal, those who have the most to lose by giving up their beliefs are less likely to apply effective skepticism to their ideas than those who have less to lose. (pp. 67-68)

CONCLUSION

Wow, John’s list gave me a lot to write about. I’ll finish commenting on his list tomorrow. To sum up, I think that John identifies the common reasons why people might be tempted to believe, but some of these seem like real secondary benefits, not mistakes – that is, they may not be good reasons to believe, but they are not deficiencies, per se.